Library Reference Number: 252

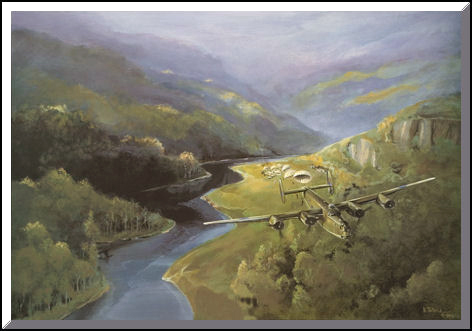

No.357 Squadron Burma Drop

Painting History from Memory of Those Who Made It

No.357 Squadron RAF was a special squadron, involved in the supply of covert forces behind enemy lines during World War Two in South East Asia Command. Formed on 1st February 1944 at Digri, Bengal, and having special requirements in order to carry out special duties, the squadron was equipped with a variety of aircraft including B24 Liberators, Lockheed Hudsons, Catalinas and Westland Lysanders.

Catalinas were used to land or retrieve agents from the long coastline of Japanese occupied territory while the Lysanders’ task was to extract agents from Japanese held territory.

However, this article deals with a rear gunner who flew in Liberators, and in the absence of photographs due to the secret nature of their missions, attempted to recall his experiences from memory. P/O Walter McDougald flew in a crew captained by Flt Lt G. Smith based at Digri, Jessore and on detachment at China Bay, Sri Lanka. While based at China Bay each operation covered well over 3,000 miles to reach distant dropping zones.

There is probably much less written about air operations in the Far East during World War Two than in other battle zones. Yet members of aircrew engaged in those missions flew possibly the longest flights of the war due to the vast distances necessary to reach targets without the usual back-up support such as air sea rescue and other supportive services. Another concern being that unlike the European theatre, the risk of escape or evading capture was most unlikely if shot down because of skin colour and language problems making it difficult to blend or become accepted into the local community.

The nature of those covert dropping zones would forever remain secret except in the memory of those who carried out Force 136 special operations, for cameras and notes were strictly forbidden.

How then could a veteran of the Burma Campaign convey to an artist his thoughts, feelings and emotions of those harrowing times if he required a realistic painting of a typical operation, when photographs of those events were obviously out of the question? This was the problem confronting both the veteran and the artist, and the following account was written by Canadian artist Rich Thistle who describes how the former rear gunner’s vision was finally transferred to canvas from distant memory and to his complete satisfaction. - Jack Burgess.

The phone rang, but I barely looked up from my easel. It’s probably for one of the kids anyway. I never answer the phone in the evening. Shawn called down from his bedroom door. “It’s for Mum or Dad!” I checked my watch. Much too late, I thought, for phone solicitation. I stayed glued to my stool. I was on a roll painting Burmese jungle, and it was starting to happen.

Jay picked up the phone. At the other end, a quiet, precise male voice was immediately apologetic. “I’m sorry to call so late Jay, but I can’t get the painting out of my mind. Would it be alright if I slipped over to see it tonight and watch Rich paint for a while? I would try not to bother him.”

Walter is such a sweetie, a refined, upstanding, soft- spoken man, with a clipped airforce mustache, and an unmistakably military bearing. Difficult to imagine him in the terribly-confined tail turret of a Royal Air Force B-24 Liberator, a Canadian tail gunner in the Burma theatre. Eleven hours out and eleven hours back without ever seeing any part of his own aircraft. Twenty-two gruelling hours divided exactly in half by the sudden mushrooming of eight parachutes, a few supply canisters and men dropped at sunset behind enemy Japanese lines deep in the Burmese jungle.

Small wonder he was excited, too excited to stay away. The painting he had commissioned was well under way and he somehow wanted to be there to share in the birth of his memory piece, the commemoration of his service almost half a century ago. He did come that evening and we chatted again as I worked. I understood his anticipation. It was somehow charming.

Walter MacDougald's painting, 357 SQUADRON BURMA DROP, was finished in about four weeks total time, from first conversation to final acceptance. In a way, it represents an extreme example of why many artists do not like to take commissions, although I am not one of them. Walter was directly and continuously involved in all concept aspects from the beginning to the end. His commissioned painting took the shape of his own very definite and vivid memories: everything from the character and topography of the hills and rivers of the Burmese jungle to the number of chutes released over the marked drop zone. It was one of the most “directed” paintings of my aviation career. I think this is the aspect many artists find objectionable. Artistic license is often held well in check in commissioned works of historical themes, especially when primary research is (literally) at hand. I too must admit to a certain chafing at the bit at times.

But, the privilege of painting history from the direct and vivid memory of those who actually made it far outweighs any sense of restriction I might personally be subject to. Not that all participants in World War II Canadian flying history have infallible memories. Far from it! I spent three months trying to confirm the color scheme of the Baltimore medium bomber in which my friend Tom was shot down over North Africa. I thought it would be standard desert camouflage, but had to find confirmation. I have learned the hard way not to guess about such things. One day, in mock exasperation, I chastised Tom for his lack of visual memory. “Surely you must remember the color of your own aircraft,” I said. “I flew it from the inside,” he retorted. The color scheme was finally confirmed and the painting successfully completed.

Yes I do enjoy painting commissions. In fact a sizeable number of my aviation paintings are painted to order. Many are commissioned by mail or email, although I prefer to make first-person contact with the commissioner and ideally with the aircraft, if possible. Often, I will meet someone at a show who is drawn to my work, and a few weeks or months later a letter, fat with photos, arrives. It is always an extra challenge to come up with a concept which both pleases the commissioner, and excites and inspires me.

But whether it’s a commission in acrylic on board, or in watercolor on paper, for me the excitement and challenge of making the images remains high. And even though there are a lot of good aviation fine- art reproductions out there, commissioning is probably the only way for an aviation enthusiast to bring his or her own personal aviation vision to life. It was rewarding for me to bring Walter’s vision to life.

BURMA DROP was eventually published as a poster commemorating the RAF bomber squadrons which flew in the South East Asia Command.

Rich Thistle

Footnote: Further articles on this subject may be viewed by referring to the following web

library index numbers:-

No. 056 “Force 136 Liberators"

No. 093 “Flying to the Limits – or Phantom Refuelling"”

No. 203 “Final and Longest Op”